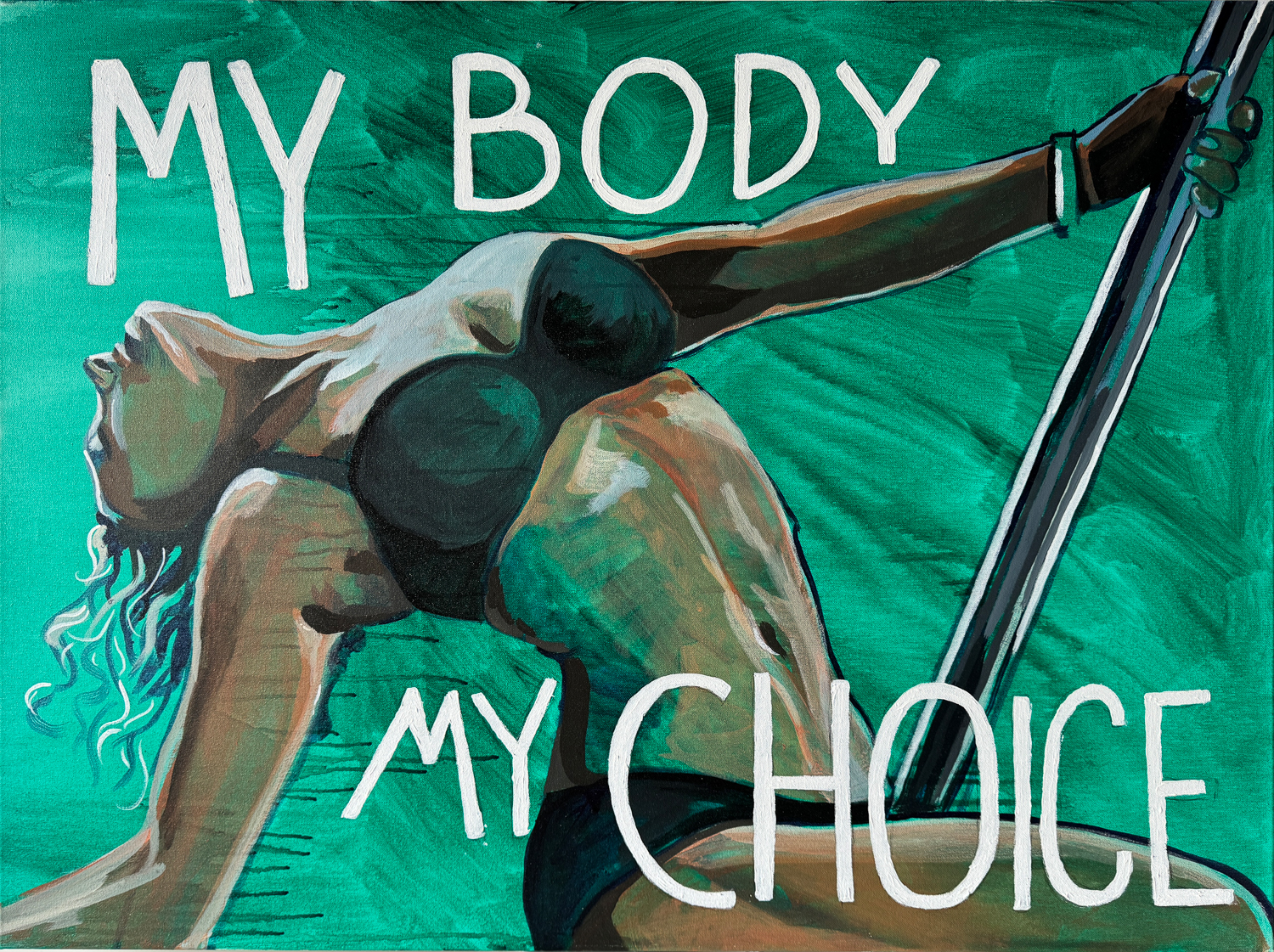

Back in September 2016, we wrote a piece about the Brooklyn Museum’s upcoming year-long collection of 10 feminist exhibits titled ‘A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism’, which launched the following month in October. Of course, we all know what happened in November, the election of Donald Trump as 45th President. While many of us were certain Democratic Nominee Hillary Clinton would win, the election completely changed many of our perspectives on the importance of art, activism, history, intersectionality, feminism and raising our voices.

Since his inauguration in January, there has been a fervent #resistance movement that has seen people becoming more energized than ever to defeat hate, division, and fear-mongering which were signature epithets of the Trump campaign. With all of this as a backdrop, it made us realize just how vital exhibits like ‘A Year of Yes’ really are, in aiding the collective consciousness when it comes to understanding why activism is so important.

One of the featured exhibitions, which launched on April 21st and runs until September 17 is ‘We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85’ which focuses on the work of more than 40 black female artists, and examines the political, social, cultural, and aesthetic priorities of women of color during the emergence of second-wave feminism, according to the description on the Brooklyn Museum website.

“It is the first exhibition to highlight the voices and experiences of women of color—distinct from the primarily white, middle-class mainstream feminist movement—in order to reorient conversations around race, feminism, political action, art production, and art history in this significant historical period,” says the Museum.

Included in the exhibition are sculptures, photography, mixed media, performance pieces, film, and more. It has been organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Family Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and Rujeko Hockley, former Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art, Brooklyn Museum.

In an interview with Dazed Digital, Catherine talks about being a white women fed up with white feminism, and how she has been championing the work of underrepresented black women especially when it comes to the foundation narratives around second wave feminism. Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff aptly points out how the focus on the work and voices of black women is important in the current political context.

“It feels especially necessary in an era when the political tide is turning venomously against people of color and women in the United States. [On May 5th] Donald Trump released a signing statement questioning whether key funding sources for historically black colleges were constitutional, and if his ghastly healthcare bill goes through it’s a matter of fact that women of color would be disproportionately affected. Even the Women’s March, which was supposed to unite feminists the world over in the era of Trump, has been legitimately called out for failing to embrace intersectionality,” he wrote.

Catherine Morris says she wants people to know that black women’s activism and the concept of intersectionality isn’t necessarily new, it has just been pushed to the sidelines.

“We wanted to do an exhibition that really expanded the narrative and history of feminism…Most white people’s understanding of second-wave feminism is as a middle-class, largely white movement. And we know that’s not true. There was lots of different kinds of feminisms emerging at the same time, even if they weren’t necessarily using the word feminism,” she said.

She sees the current political climate being a great motivator for people who want to come and see the exhibit, especially young women of color who have been talking about it a lot on social media – something she hasn’t seen a lot of during her time as curator for the Museum. Yet she welcomes the younger generation’s desire to learn the history of these women.

“When we started this exhibition there was no way we could have known the result of the recent US presidential election. Black women largely voted for Hillary Clinton and there are these ghastly statistics about these white women voting for Trump so it points to the contested lived experiences that are still present. That were present in this show and that live on,” she said.

Although she welcomes the increased amount of social media attention being given to the exhibit, Catherine does stress that seeing it in person is far more informative than simply sharing an image to a page.

“There’s a lot in the exhibition that is interesting and enlightening. The fact that in 1977, the Combahee River Collective, a black lesbian feminist organization, wrote a statement that basically presages this whole idea of intersectionality in a brilliant kind of way. What we’re talking about today is contained in this history,” she said.

Intersectionality is still a new term for many feminists today, and gaining an understanding of what it means from earlier feminist activists whose lives very lives were the intersection of a number of issues (race, class, gender, sexuality, etc) is a great place to start, especially for younger women today who are looking to be part of the feminist movement.

“Feminism can exist in many different ways. Women, well before this period even, have always found ways of engaging ideas about feminism. One of the significant differences to me between what we call ‘whitestream feminism’ that really appears in the exhibition, is that the women weren’t just focused on the rights of themselves in relationship to gender equity. They were focused on their families along with them. Feminism for women of color wasn’t about getting the next good job. It was the much closer relationship to other rights movements – particularly Civil Rights obviously – but sometimes gay rights or disability rights. They intersected and they weren’t discrete. Class issues and economic issues were also incredibly tied in to all these discussions,” said Catherine.

Some of the artists featured in the exhibit include filmmaker and Beyoncé influencer Julie Dash, painter Emma Amos and southern vernacular artist Beverly Buchanan. Many of the women were activists in the Civil Rights movement, Black Power movements, Women’s Rights movement, the Anti-War Movement and the Gay Liberation Movement in America.

We highly recommend going to see ‘We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85’ at the Brooklyn Museum while it is being shown. Art has always been an important voice in resistance movements, and today’s climate is no different.

2 thoughts on “Brooklyn Museum Celebrates The Activism Of Radical Black Feminists From The Second Wave In New Exhibit”