By Lauren Speeth

As a judge of student films, I have a sense of what’s on students’ minds, or at least the ones who submit to Campus Moviefest, The World’s Largest Student Film Festival, where we have a Hope in Social Justice award. Last year, over 530 films made it through to final judging in that hope-filled category. That’s a lot of films, even at only five minutes each. Meeting the student filmmakers at the finalist screening is a highlight, as they share what motivated them. Lately, one thing that’s been on their minds is mental health.

This year, the winning film was on teen suicide. It’s called ‘The 25’, and if you watch it, I bet you’ll never forget it. It got me thinking about suicide, hope, and resilience. What has suicide got to do with hope? Everything! Hopelessness is a strong predictor of a suicide attempt. Visible signs of hopelessness include: speaking of a bleak future or death; giving away possessions; neglecting appearance; risk-taking; losing interest in activities; abrupt calm or good mood; getting affairs in order; saying goodbye.

Taking these signs seriously could save a life. And we can consciously grow hope. We can choose to help our young people believe in their futures by investing in them and in the world that they are inheriting. That won’t solve suicide, but it will weed out one of the root causes: hopelessness.

Then, there’s resilience, meaning the capacity to spring back from setbacks rather than being crushed by them. Dr. Gary Slutkin, an expert on contagion, has noticed something very wonderful about resilience in society. Because violence acts like a communicable disease, it can be interrupted, purposefully. With skilled care and effort, we can bounce back from it. Consider post-WWII England, where a change in the formulation of gas to kitchens interrupted a trend in suicides, and the overall rate fell sharply and permanently.

With the opportunity removed, society bounced back. A study from Harvard points out how a crisis can be short-lived, and that nine of ten people who make a suicide attempt survive and don’t go on to die by suicide later. My thoughts turn to resilience, and what might happen if we reduced access to the deadliest methods available.

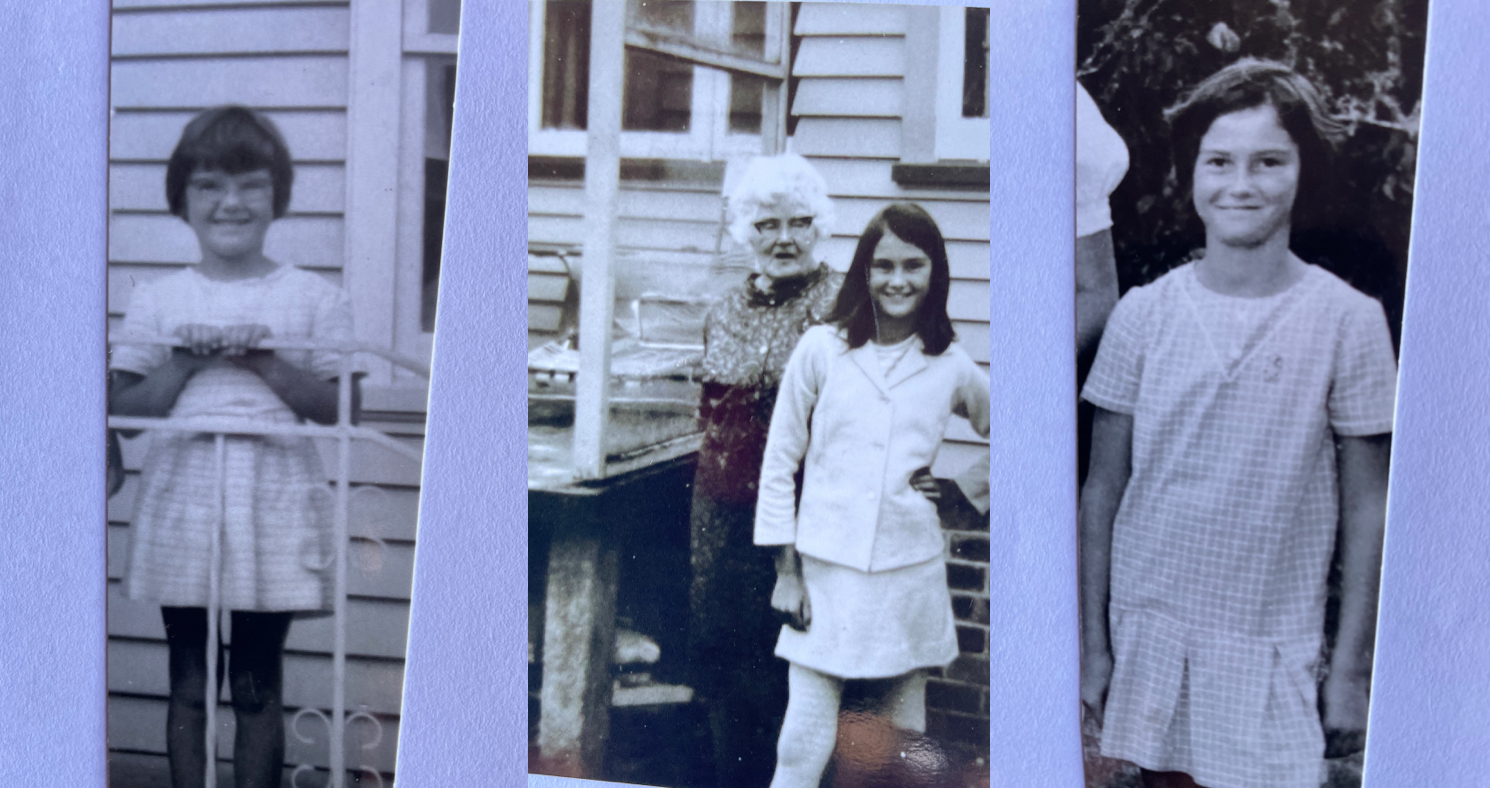

A few years ago, when I was exploring the idea of trying my hand at historical fiction, there was a spate of teen suicides near where I live. It felt like a contagion that needed an antidote. I’m not a doctor, I’m a storyteller, and I’m keenly aware of the power of one idea to fight another. I thought back to my own teenage years, and how much my own resilience was influenced by the sci-fi characters in worlds that had nothing to do with my own. I decided that one goal for my novel ‘Thread for Pearls, A Story of Resilient Hope‘ would be to delve into thoughts, hope, hopelessness, and what makes someone resilient.

I could address some of the challenges of growing up in a way that might speak to a young reader, even though the novel is set decades before they were born. In my novel, I touch on many relatable challenges, and mirrored life’s ups and downs with unsettled travel: takeoffs and landings, and even a few voyages at sea. The book itself opens with a car crash, as if to portend a bumpy ride, which is what life is so often like for so many of us. And three of the main characters have brushes with suicide: the main character Fiona, her father, Wolf, and her older sister, Karen.

Wolf is a bit of a mad scientist who’s having trouble dealing with a real-world marital breakdown and decides to put himself in harm’s way. He ignores a riptide warning sign and dives into the ocean, where he’s flung under mighty waves and pulled out to sea. As I noted earlier, risk-taking can be an indication of hopelessness. Hearing his daughter’s cries for help reignites his will to live, and he swims to shore:

Wolf dragged himself out of the surf, sandy and pale, his chest heaving. Fiona noticed the chill bumps on his skin and that he had lost his swim trunks. Turning her head away so he could have some privacy, she handed him a towel, which he accepted and wrapped around his waist. “Riptide, Fee. Just like the sign.” He’d seen the signs, and gone in anyway, and put himself in harm’s way knowingly. Still, the thought didn’t cross Fiona’s mind that he might have been trying to kill himself that day. She had no idea how close he’d come to giving up hope. She just thought he was a daredevil. “Good thing you’re a strong swimmer, Pop.” “Good thing,” said Pop.

The second character to have a brush with suicide is Fiona’s older sister, whom we learn has once been hospitalized for an attempt. The family is afraid to share this information with Fiona, for fear of a copycat attempt. The reader is left to wonder whether Fiona will carry on in her older sister’s footsteps or find a way to forge ahead with life. By the time Fiona reaches college, she’s a bit bruised, and a little fragile. Suicide as a concept is not foreign to her. She’s attended the Broadway play ‘For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf’, by Ntozake Shange, an African-American feminist poet and playwright, and taken in newspaper reports of a “mass suicide” in Guyana.

Fiona considers suicide, too, for her own reasons. But remember, this is a novel of resilient hope. You didn’t honestly think for a minute that I’d kill off my main character that way, did you? In ‘Thread for Pearls’, I include gun violence, attempted suicide, inept parenting, and some concerned friends who don’t quite know how to react to it all. True to the times, I tell how suicide was once illegal, treated as “attempted self-murder,” rather than an expression of mental anguish. Back then, if a person succeeded, they were often denied a religious service and burial. And if they didn’t? They might be thrown in jail for trying. Today, both religion and the law are more humane.

As I look over the many student movies on mental health issues, it seems to me that stigma is falling, as well. That’s great news, because as stigma recedes, more students might be willing to seek help rather than suffering in silence or taking drastic action. I often return to our playlist of winning films, for a shot of hope and resilience. As I contemplate how our world is in such great hands with them, I get such a boost. I’m glad they got me thinking about suicide, resilience, and hope.

Lauren Speeth has shared her stories in film and print over the years with audiences around the world, to critical acclaim. Her diverse storytelling interests cover many mediums: from books about the American experience to 3-D films about Irish spirituality, to music about love and life. In this, her first novel, she shares what she has come to understand as the fundamental human experience of resiliency and hope. When not dreaming up stories, Speeth leads Elfenworks Productions, LLC, a pro-social business with internationally acclaimed media content, and The Elfenworks Foundation, where she has assembled a team of social entrepreneurs who work together daily on projects that foster the greater good.

2 thoughts on “Author Weaves In Themes Of Hope & Resilience To Tackle Teen Suicide In Debut Novel”