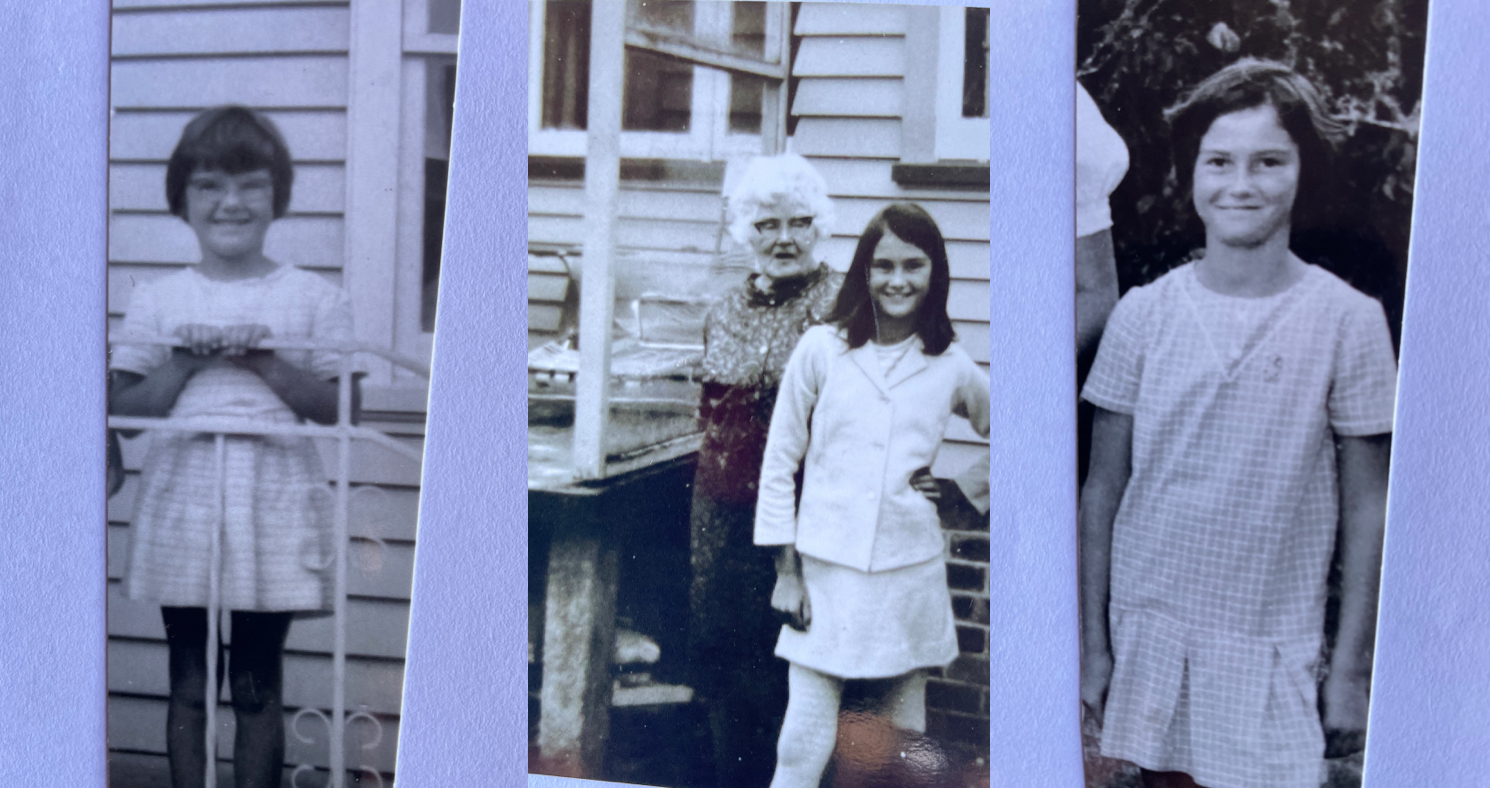

The following is an excerpt from ‘Shrug’, a book by Lisa Braver Moss, out on August 13 from She Writes Press. The novel follows a Vietnam War-era teen whose family life is just as chaotic as the anti-war protests filling the streets of her hometown. While writing the story, Lisa drew on her own experience as a survivor of domestic violence who came of age in Berkeley during the seismic ’60s to craft the novel’s lead, Martha, who develops a nervous tic (a shrug of the shoulder) while waging a private rebellion as her peers take part in a very public, nationwide movement.

Martha Goldenthal isn’t your typical 1960s Berkeley radical. Her rebellion isn’t sex, drugs, or rock ’n’ roll—it’s doing well at Berkeley High and planning for college. Her father, Jules, is a raging batterer who, because of his own insecurities, hates academia. Not that her off-the-rails mother, Willa, is much better. Meanwhile, Jules’s classical record store, located directly across the street from the U.C. Berkeley campus, is ground zero for riots and tear gas. No wonder Martha has a nervous tic—a shrug of the shoulder.

Preoccupied with the family situation and barely able to concentrate, Martha plods along in school and somehow manages to achieve. But her parents’ hideous divorce, the loss of her father’s record store and livelihood, a heartless eviction from the family home, and an unlikely custody case wind up putting Martha in Jules’s care. Can she stand up to her father and do the one thing she’s sure she must—go to college?

With its running “soundtrack” of classical recordings and rock music and its vivid scenes of Berkeley at its most turbulent, “Shrug” is the absorbing, harrowing, and ultimately uplifting story of one young woman’s journey toward independence.

I put my books down on Principal Scranton’s desk and saw him glance at them: Latin for Beginners, Advanced Algebra, English Composition, Concert Chorale music.

I sat down. Mr. Scranton closed the door, came around the desk and sat down across from me. “What can I do for you?”

The lack of accusation almost made me want to cry. “I’m Martha Goldenthal,” I began.

“Goldenthal,” he repeated, just as Mrs. Worth had done. Did his eyes flicker? “You’re Hildy Goldenthal’s sister?”

“Yes. My mother—” I couldn’t help it, I started weeping.

Wordlessly, Mr. Scranton handed me a shallow box of Kleenex like the kind I’d seen in the pediatrician’s office. “I was sick for two days. And my mother wouldn’t write me a note, because she said it was my fault I got sick.”

“Oh!” Mr. Scranton said.

“Plus, I think maybe she was mad because I didn’t want to eat barley stew for breakfast. Which, I mean, she worked hard on it, I guess, plus she had to go to the store for all the ingredients. But it just made me gag, I couldn’t help it—” I swallowed, trying to focus. “Mr. Scranton, I tried to explain the rule to her, that if I didn’t get a note, I’d get an unexcused absence. But she just—”

“I understand.”

“Maybe you could try calling her at home—” Wait, he understood? Shrug. I glanced vaguely in his direction, but he wasn’t looking at me anymore and didn’t even seem to be listening. He was scribbling something on a small notepad.

“The last two days, you say? Wednesday and Thursday?”

“Right, but—”

“Take this to your first period teacher,” Mr. Scranton said as he finished the note and tore off the little sheet. He got up and crossed the room, opening the door for me. Then he patted me on the shoulder—run along, now, with a little comfort mixed in.

I wasn’t happy with Mr. Scranton’s solution. I wanted to be in trouble for having two days’ worth of unexcused absences and half a period of lateness. I wanted him to call my mother and see for himself how crazy she was, what a horrible person, someone who hated her own children. I wanted to tell him that when I read things, I didn’t understand them—that the good grades were a kind of parlor trick I could do, like knowing what key a piece was in, and that I was worried to death someone was going to find out I had no substance. Most of all, I wanted to ask why Mr. Scranton had let me off the hook.

But I was late, and now wasn’t the time to be curious. Now was hardly ever the time to be curious.

You can learn more about Lisa Braver Moss and ‘Shrug’ by visiting her website.